The ‘Forgetful’ Rider

You’re coaching a rider, you say, “Turn left at the cone, then trot down the long side.” They nod, but moments later, they blow straight by the cone instead of turning. The next lesson you’re focusing on having the rider look before the turn and their hands are down in the horse’s mane. You gently remind them to pick your hands up. A minute later, their hands drop again—not because they’re ignoring you, but because the instruction seems to vanish from their mind 10 seconds after it’s said.

If you’ve experienced moments like this, you know how frustrating and confusing it can be. What’s really happening is often less about effort or attention and more about working memory—a crucial mental process that helps us hold and use information in the moment.

What is Working Memory?

Think of working memory as the brain’s mental dry-erase board giving the freedom to note, move and change things around. It’s the system that allows us to temporarily hold and actively work with information while completing a task.

Unlike short-term memory, which briefly stores information, working memory is active—it helps us process, manipulate, and connect information. And unlike long-term memory, it doesn’t store things for future use.

Working memory capabilities vary widely from person to person, influenced by factors such as age, experience, and individual brain development. For some individuals, especially those with ADHD, autism, TBIs or other learning differences, working memory can present greater challenges. These differences can affect how easily they hold and process information in the moment, making tasks that require quick thinking and multi-step instructions more difficult. Understanding this variability is important for tailoring support and teaching methods to meet each rider’s unique needs.

Why is Working Memory Important for Riders?

Riding isn’t just physical—it’s a cognitive-motor activity. In a lesson setting, riders need to:

- Remember and apply instructions

- Coordinate their aids to influence the horse

- Respond to the horse’s movement and behavior

- Learn and recall patterns, courses, or obstacle sequences

- Potentially navigate other horses or people moving around in the space

As riders progress, the demands on their working memory grow. At first, it may be as simple as “turn the horse.” Later, it becomes “use the inside leg at the girth, maintain contact with the outside rein, and bring your outside leg just slightly behind the girth to support balance through the turn.” That’s a lot to hold in mind at once.

Signs a Rider May Struggle with Working Memory

Watch for these indicators in lessons:

- Forgetting instructions quickly

- Needing frequent reminders or demonstrations

- Struggling to recall patterns, courses, or games

- Becoming overwhelmed with multi-step tasks

But also note, even riders with strong working memory can have difficulties under stress, fatigue, or distraction.

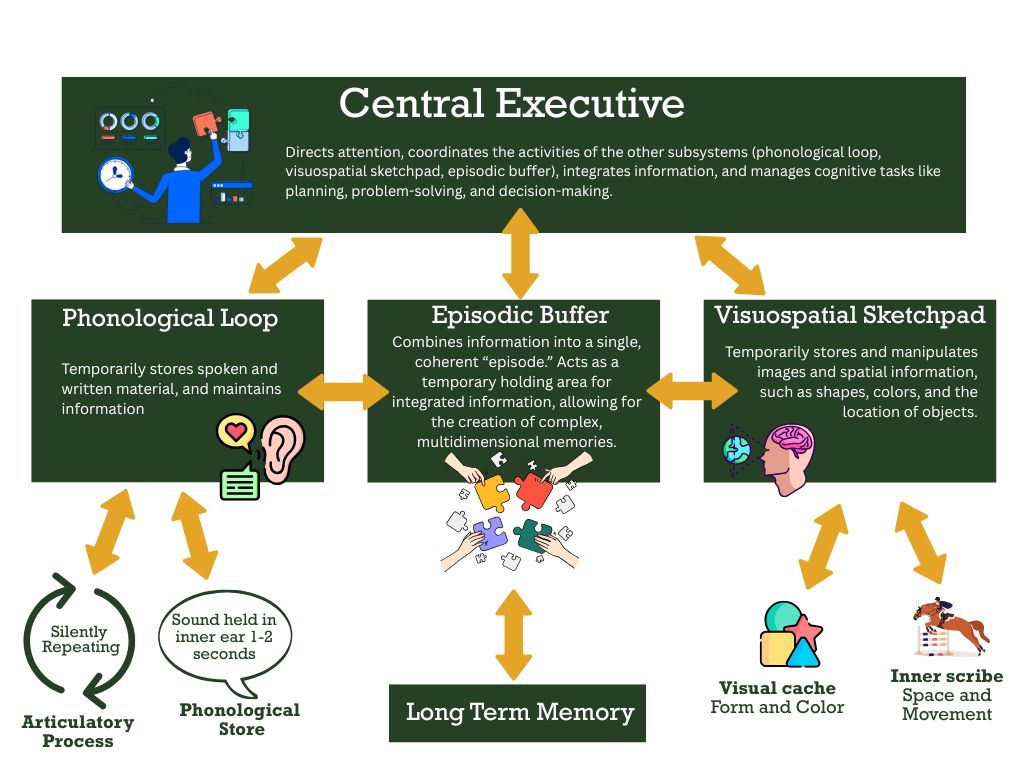

How Working Memory Works

The Baddeley and Hitch model describes working memory as a system with four parts that function like a mental workspace:

- Central Executive: The “manager” that focuses attention and coordinates the other parts.

- Phonological Loop: Handles words and sounds, such as “ride to M and Halt” where the rider might repeat over and over in their head “Halt at M”.

- Visuospatial Sketchpad: Deals with pictures and spaces, such as visualizing where their hands should go or how to ride across the diagonal.

- Episodic Buffer (added later): Combines sights, sounds, and feelings into a single memory and connects it to long-term memory.

For instructors, understanding how these systems work can make it easier to adjust teaching methods and support riders more effectively by teaching with methods that support their current strengths.

Supporting and Strengthening Working Memory in Riders

As instructors, we can make lessons more memory-friendly while also helping riders develop stronger working memory over time. These strategies support riders in the moment and build their capacity to hold and process information:

- Simplify Instructions

Break tasks into 1–2 simple steps to avoid overloading the rider’s mental workspace. - Repeat and Reinforce

Have riders repeat instructions back to you, or use call-and-response to strengthen retention. - Chunk Information

Teach complex patterns or sequences in small sections, then link them together. For example, introduce two fences at a time in a jumping course before riding the full course. - Use Visual and Physical Cues

Markers like arena letters, cones, poles, and even riding alongside providing a demo can provide helpful reminders. Drawing patterns in the dirt or using pictures and signs can also reduce memory load. Give them a visual example of aids or body positioning. - Visualization

Ask riders to trace their eyes to where they are going to go. For some, using creative imagery such as “slithering like a snake through the cones” or “riding that turn like a rainbow” can be helpful. - Checklists and Routines

Establish repeatable warm-up routines or pre-ride checklists to make multi-step processes more manageable. Have that checklist visible and accessible to use until it’s a well established routine. - Play Memory Games

Playing things like “Simon Says” or “Add-On” games with riding aids and movements are fun ways to strengthen memory in the context of a lesson. Start with one pole, then add one more pole each repetition to build a whole course. - Active Reflection

Encourage riders to draw the pattern they just rode or explain what skills or aids they used out loud. Older students might benefit from keeping a riding journal to record key concepts, aids, skills etc. - Diversify Teaching Methods

Use a combination of teaching methods such as visual examples, spoken and/or written directions, tactile prompting, and spatial targets to play to each rider’s strengths. - Limit Multitasking and Manage Distractions

Avoid giving instructions while riders are in the middle of actions or thoughts. Simplify the arena environment for easily distracted students, and use a “pause and reset” moment when they seem overloaded. - Engage Multiple Senses

Combine verbal, visual, and kinesthetic cues to reinforce learning. For example, say the instruction, and have them point to where to go. Something like, “as you round that corner, I want you to look to smell the pine trees on the other side of the ring.” - Encourage Healthy Habits

Hydration, rest breaks, and light stretching not only help riders physically but also support their brain’s ability to process and retain information.

By weaving these techniques into your lessons, you can help all riders succeed while building their ability to hold and work with information more effectively—both in the saddle and beyond.

Why This Matters

Understanding how working memory affects learning allows for instructors to teach with more patience, creativity, and success. This is especially important for instructors who are teaching young riders and those who teach riders with more diverse learning needs. With small adjustments, you can help students build confidence, stay engaged, and develop both their riding and cognitive skills in a healthy and fun way!